An AI assistant with system privileges: what could possibly go wrong?

Nobody asked for a handset possessed by its own AI. ByteDance built one anyway.

In the past week, as far as China’s tech circles are concerned, few things have been discussed with more anticipation and more unease than ByteDance’s new Doubao Mobile Assistant.

The company calls it a system-level agent, but this is not China’s first attempt at such a creature. Xiaomi, Honor, and Oppo’s Breeno all once flirted with device-anchored agents before. Doubao Mobile Assistant is different. It arrives not as an extension of a handset brand but as a product of China’s most formidable attention machine.

The last time ByteDance ventured into phones, it did so through Smartisan, the quirky Chinese handset maker whose patents and staff ByteDance acquired in 2019. That effort produced a single device, the Smartisan Jianguo Pro 3, briefly marketed as a “Douyin phone” for its deep integration with ByteDance’s video apps. The project never expanded into a sustained hardware strategy, and much of the original team was eventually absorbed into other ByteDance units, including education.

This time, ByteDance did not attempt to build a phone of its own. Instead, it created an experimental operating environment and deployed it inside someone else’s hardware.

Through a partnership with ZTE, Doubao appeared inside a modest Nubia smartphone priced at 3,499 yuan (US$482). It sold out on day one, not because of the phone itself but because buyers wanted to glimpse what happens when an AI is allowed to live inside a handset rather than merely accessorize it.

In fact, the Doubao team has already been moving toward this moment for some time. On PC and Mac, their AI assistant already has the power to read screens and perform automated actions.

Luxuries made possible by the relative openness of desktop systems. Smartphones, however, operate with tighter boundaries. Without system-level injection, any agent, no matter how intelligent, is confined to its own sandbox.

And this is where the double edge shows. On mobile, the question is almost never about what the agent can do. It is about who watches the agent once it is permitted to move on its own.

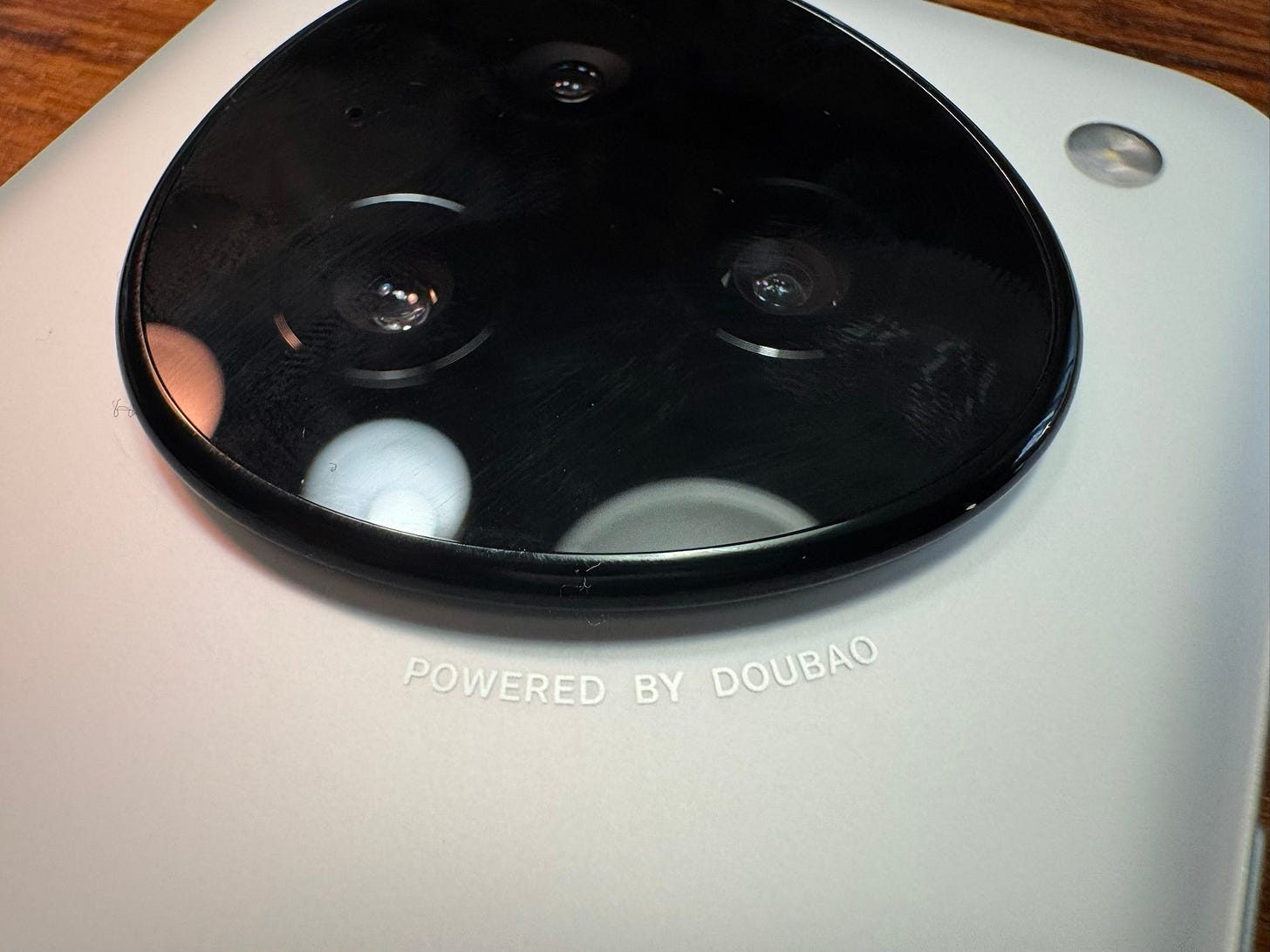

I luckily snatched a unit of the Nubia M153 before it was gone. ByteDance insists it is only an engineering prototype, a vessel for the assistant rather than the beginning of a Doubao Phone line.

It comes with a Snapdragon 8 Elite Gen 5 processor, a 6.78-inch LTPO display, 16GB of RAM, 512GB of storage, a 6,000mAh battery, NFC, infrared, and a silver-white chassis punctuated by a physical button designed for one purpose: summoning the Doubao AI. Also, the phone runs Obric UI, ByteDance’s customized environment for this experiment.

In demonstration videos circulating online, Doubao behaves like an invisible “roommate” with inexhaustible patience.

Ask it to compare the price of a chicken sandwich across Meituan, Taobao Flash Sale, and JD.com, and it slips silently into each app. It searches, taps, logs, and returns with a tidy summary. Instruct it to place the order and forward a screenshot to a friend on WeChat, and it does so with clerical devotion. The only step still reserved for you is the moment of payment, a boundary the assistant has not yet been invited to cross.

In my own tests, the device lived up to its viral reputation. It could swipe through TikTok videos on its own, fill in online quizzes, and perform actions that felt not dangerous exactly, but unsettling in their plausibility. A simulated bank transfer, for instance. It never entered the password, since Doubao does not yet impersonate the user’s hand to that degree, but it maneuvered seamlessly to the threshold of transfer, as if waiting for a quiet nod of approval.

Still, none of this qualifies as magic. Doubao works because it sees the screen, identifies UI elements, and takes over the gestures that would otherwise require a human finger. It is not communicating with apps through underwater interfaces. It is just impersonating the user, frame by frame, tap by tap.

And that impersonation quickly became a problem. As the Nubia M153 reached more users, major Chinese apps began to reject it outright.

WeChat temporarily blocked logins from the device. Alipay and several banking apps followed, either through active bans or through automated risk-control systems that detected unfamiliar patterns and locked users out.

For a moment, it felt as though the country’s most widely used apps were pushing away a foreign body, not because the device was faulty but because it behaved too much like a person. Or perhaps too little.

What Doubao attempts to embody is what the industry has begun calling agentic AI, a category of intelligence that no longer waits for the user to tap their way through an app but instead performs the task itself.

In the Chinese imagination, this promise has been circulating in the last 3 years. Every major smartphone keynote has gestured toward a future where the phone becomes an active collaborator rather than a passive tool, a kind of digital aide-de-camp that can navigate the fragmented landscape of apps on behalf of its owner.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Doubao does not reinvent what an AI assistant is supposed to be. It simply carries out a familiar vision with a level of completeness that previous attempts never reached. What makes it feel new is not the idea itself, but the distance it is willing to travel to make that idea actually work on a modern smartphone.

That distance becomes clearer when placed next to Apple and Google. Their approaches differ not in technical capability but in philosophical posture.

Apple Intelligence, introduced with no shortage of ambition, still behaves like a cautious house guest. It suggests, summarizes, polishes, and retrieves, yet avoids touching anything that might belong to someone else. Google’s Gemini, even when deeply embedded into Android, operates through carefully negotiated APIs. It speaks to apps through doors left politely half open. The boundary between assistant and application remains intact, preserved by a kind of tacit social contract.

Doubao operates as if no such contract exists. Instead of waiting for app makers to build integrations, it studies the screen directly and decides what to do next. The difference is subtle but consequential. Apple and Google designed assistants that ask apps for permission to help the user. Doubao assumes that the user’s request is permission enough.

For anyone watching the evolution of AI on mobile devices, the arrival of Doubao marks a moment when the future forks. One path favors assistants that remain deferential, bound by formal integrations and explicit trust structures. The other imagines assistants that act first and justify their actions through results.

Doubao chooses the second path, not because the vision is especially radical, but because it takes the fastest route available. In a landscape where every major app operates as a walled garden, the only way for an agent to function today is to slip between those walls rather than wait for doors that may never open. The approach works, but in the same way an iOS jailbreak works: as a hack, driven by impatience as much as ambition. It produces striking results, yet it also raises the question of whether such a method can ever be viable, or safe, for the mainstream.

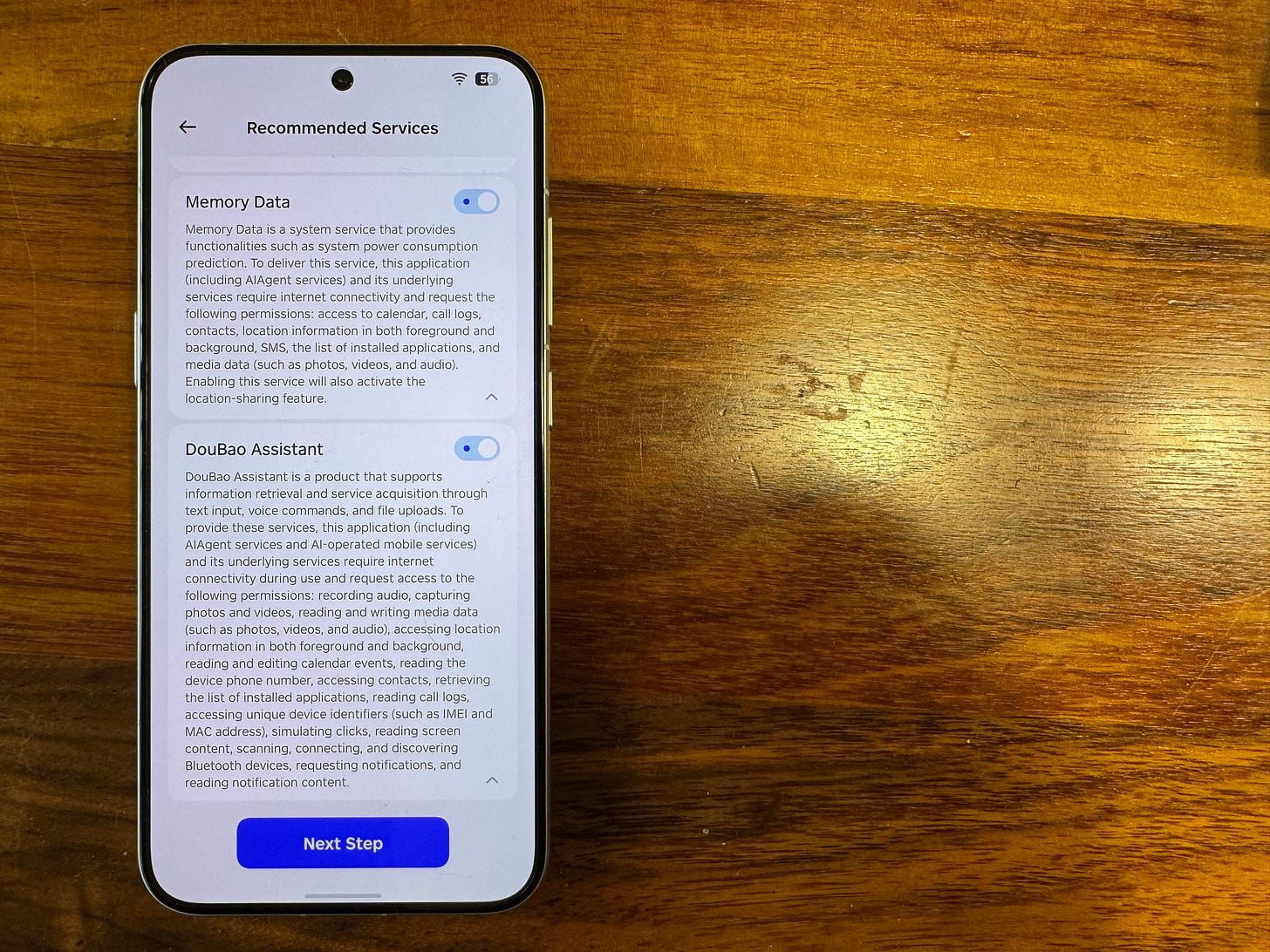

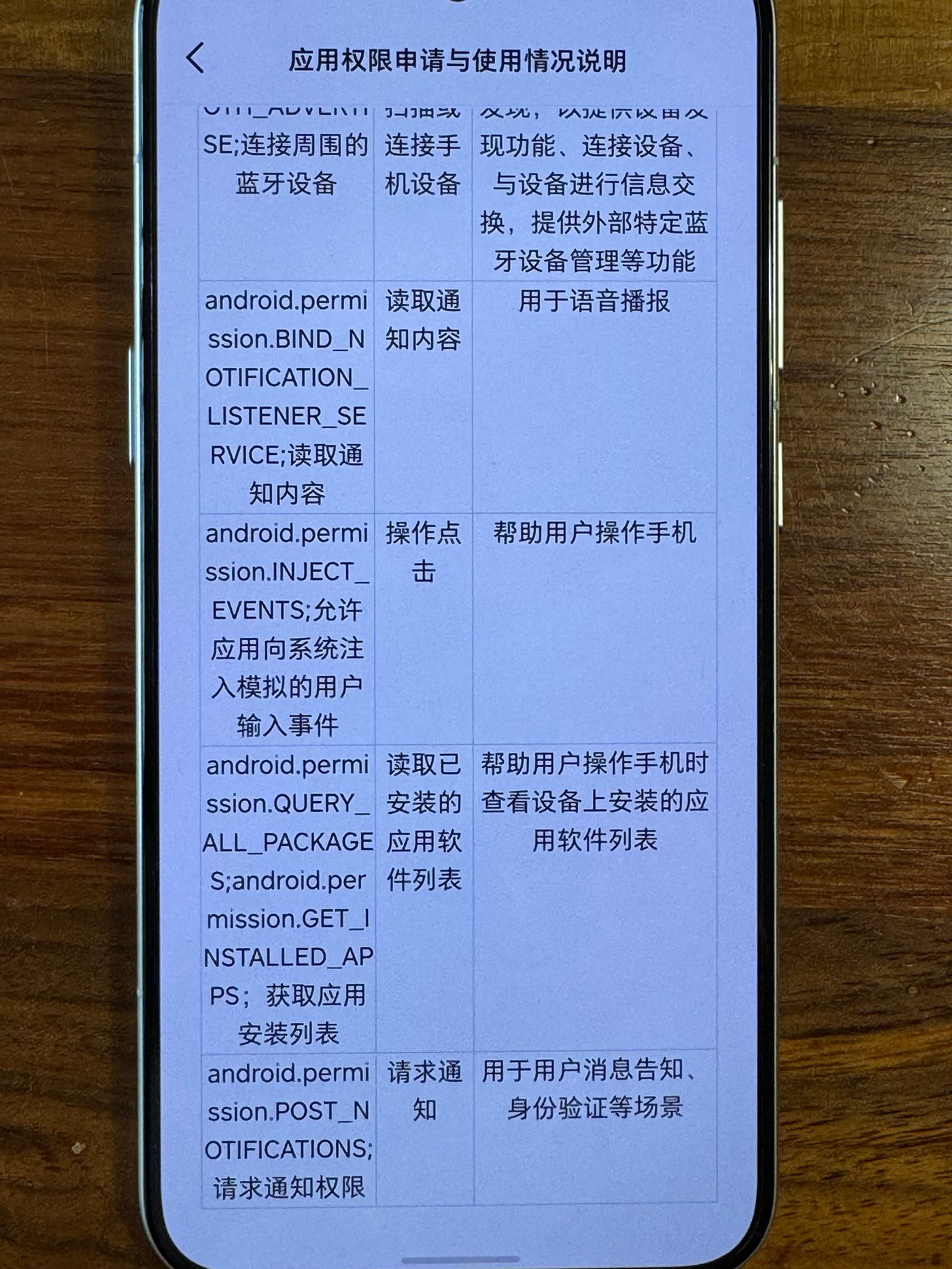

The ability to reach that far comes from a single Android permission called INJECT_EVENTS. It looks minor on paper, but it is one of the most powerful privileges in the system. Google classifies it as a signature-level permission, reserved only for components signed with the same cryptographic key as the firmware. In practical terms, the assistant is not just an app installed on the phone. It is treated as part of the operating system itself.

Most permissions open a door to a specific function. INJECT_EVENTS gives access to the entire body. With it, software can write directly into the phone’s input stream, generating touch signals that are indistinguishable from human interaction. The system cannot tell the difference, and neither can banking apps or fraud detectors.

Technically, this means Doubao bypasses the UI hierarchy and acts at the hardware level. It does not ask apps for cooperation. It simply moves through their interfaces as if it were the one holding the device.

The existence of such a permission raises a question that is less technical than structural. Why is a system-level capability like this permissible here but unimaginable in the West. The difference has little to do with engineering talent and more to do with how ecosystems define authority. Apple will never delegate this level of control to an external agent because its entire platform depends on a strict separation between the system and the apps running on top of it. Google restricts INJECT_EVENTS to manufacturers because a global marketplace requires predictable lines of trust. In both cases, the assistant is allowed to assist, but never to operate as a peer of the operating system.

This is also why Doubao ends up arriving inside a ZTE device rather than as a download available to anyone. Without firmware-level signing, the system would reject the assistant’s capabilities outright. Embedding the agent at the operating-system level is not a display of ambition so much as the practical requirement for how this particular model of assistance is built. It is less about breaking rules and more about bypassing the structures that were never designed with agents in mind.

The contrast becomes even sharper when placed next to the path Apple and Google have been taking. Both companies have spent the past few years building what they call Intents frameworks — Apple’s App Intents and Google’s expanding library of system-level intents. These frameworks move slowly and often feel frustratingly limited, but their premise is straightforward. They create permissioned, auditable pathways through which assistants can request specific actions without overstepping application boundaries. The assistant does not impersonate the user. It negotiates through a shared vocabulary that the ecosystem has explicitly agreed to honor.

From afar, this looks conservative. In practice, it reflects a belief that cross-app automation only becomes sustainable when the rules are explicit and the lines of authority are preserved. App Intents represent a long-term path. It is slower, but it does not require the assistant to jailbreak the operating system to get work done.

By comparison, Doubao’s method feels like a short circuit: effective, even elegant in its way, but undeniably a hack. It reaches for outcomes the ecosystem has no native protocol for, filling the gaps with system-level privileges that were never intended for agents. This makes the device impressive in the short term and difficult to justify as a mainstream model in the long term.

The more time I spend with the device, the clearer it becomes that Doubao is not simply illustrating what an AI assistant can do. It is illustrating what happens when an assistant begins operating outside the boundaries that apps, platforms, and users once assumed were fixed. Its power is not a side effect. It is a structural consequence of an ecosystem built from many self-contained worlds that do not willingly speak to one another.

In that environment, any agent that hopes to function must cross walls that were never designed to be crossed. Doubao does so with an ease that feels impressive at first and unsettling immediately after. The discomfort is not because the assistant is misunderstood. It is because its method—reading every screen, acting as the user at every layer—is fundamentally indistinguishable from overreach.

If anything, the ecosystem’s resistance is not misdirected. It is a reminder that capability and legitimacy are not the same thing. A system-level agent that navigates financial apps, social platforms, and private content on behalf of the user without the consent of those apps is not merely innovative. It is introducing a new political reality into mobile computing, one in which the operating system can quietly overrule the autonomy of every application in its path.

Doubao is, without question, the most competent mobile agent I have ever used. But its competence exposes something larger. Perfect automation in a fragmented ecosystem requires a form of intrusion, and that intrusion forces us to reconsider what a phone is allowed to do on our behalf. The question is not whether Doubao succeeds. It is whether the model it represents should exist at all.

The future of AI on mobile devices will not be shaped by who builds the fastest model or the most convenient assistant. It will be shaped by whether we decide that an agent acting “as us” is an acceptable default in a world where neither apps nor platforms were built to accommodate such authorit.

Excellent article! Thank you