When smarter AI means less sensitive about privacy

As AI agents rise, concerns about surveillance and trust resurface—only more urgently.

As AI agents take center stage in 2025, a quiet yet profound tension is emerging between the promise of smarter devices, systems, and applications and the peril of eroding user privacy.

Unlike LLMs or other foundational models, AI agents represent a more advanced form of intelligence. It is no longer just about conversations. It is integration, orchestration, and decision making.

“The takeover, the break's over.”

The moment crystallized when the then Honor CEO George Zhao reenacted Steve Jobs’ 2007 latte ordering prank. Except this time, it was real. The AI agent took over the phone and placed an order of 2000 tea drinks on its own, echoing that viral TikTok where someone buys a Porsche by accidentally splashing water on the screen.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

In China, this AI agent landscape is more than that, it takes shape along three major lines:

Device-anchored agents embedded in smartphones, robots, and glasses (just like the Honor phone does);

Platform-based agents developed by major tech players such as ByteDance, Alibaba, DeepSeek and so on;

A vibrant ecosystem of startup-driven applications, with Manus among the more visible examples.

Yet the road to a mature agent economy is far from smooth. Technical bottlenecks, uneven development paths, and growing concerns over fairness and privacy have all begun to weigh on the sector's momentum.

In particular, the tension between innovation and individual rights is fast becoming impossible to ignore.

The privacy boomerang in the AI era

As AI agents grow more sophisticated, their appetite for data has expanded exponentially. Tasks that require nuanced contextual understanding have pushed many developers toward increasingly invasive data collection practices.

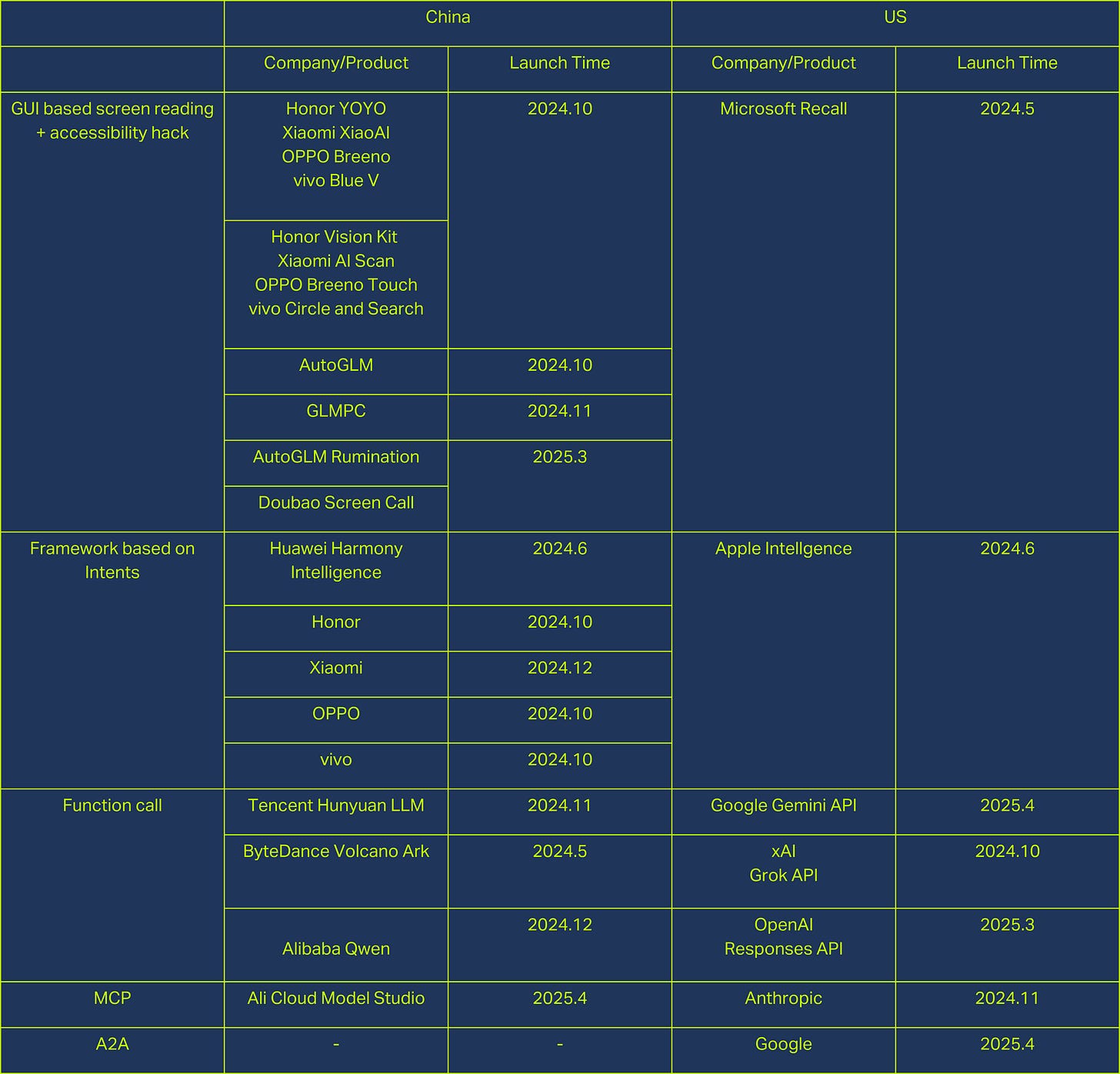

US based efforts are shifting toward more standardized, protocol driven methods, with an emphasis on privacy preservation.

In China, the trend is particularly stark: rather than building robust, consent-based architectures, many agents have opted to take the leanway in operating system permissions, especially through the abuse of Accessibility Services.

The Chinese reliance on GUI-based screen-reading techniques not only heightens user risks but also signals a broader strategic divergence that may have lasting consequences.

Screen-reading agents: a chilling privacy faultline

The smartphone has become the frontline of this silent privacy war. Beginning in 2024, companies like Honor have adopted practices that allow their AI agents to read screens and simulate user actions without the explicit consent of third-party apps (buy me 2000 cuppa tea and it did).

By misusing Accessibility Services, these agents gain near-total visibility into users' digital lives—from private conversations to banking credentials.

Originally intended to aid users with disabilities, Accessibility Services offer a powerful—and dangerously underregulated—gateway into user data. The risks are not theoretical: the same mechanisms have historically been exploited by malicious actors to siphon billions of personal records.

On desktops, ByteDance's Doubao AI assistant introduced a "Screen Sharing Call" feature in early 2025. Although pitched as an enhancement for user convenience, the feature—allowing AI to read and process live screen content—evokes clear parallels to Microsoft's controversial Recall feature.

Recall, unveiled in 2024, promised to create a searchable visual memory of user activity. Yet it immediately drew widespread backlash over its sweeping scope and potential for abuse. Microsoft was forced to delay its launch, ultimately restricting Recall to an opt in setting with strict local data controls. Nearly a year later, the company has finally begun rolling Recall out to the public, though only on high spec Copilot Plus PCs equipped with powerful neural processing units. The updated version of Recall now includes automated content filtering, enhanced local storage protections, and a clear opt in requirement—a marked improvement over its original form, though still not immune to criticism.

The echoes are unmistakable: China's new generation of smart AI assistants appears poised to repeat the very missteps that provoked such controversy abroad, with even fewer safeguards in place. On PCs, this takes the form of explicit screen sharing and content parsing. On smartphones, it is often less visible but no less invasive, with preinstalled AI features like Xiaomi's XiaoAi or OPPO's Breeno quietly capturing screen content under the guise of convenience.

In some cases, such as OPPO's "Breeno Screen Recognition," users are not even asked for consent before sensitive permissions are activated—a practice explicitly acknowledged in the platform's privacy policies.

What unites these trends is not merely the technical method but a broader disregard for user agency. Whether through overt consent or buried terms, the result is the same: the boundary between user and machine is eroding, often without meaningful oversight.

The new approach

Xiaomi CEO Lei Jun, among others, has called for reform, urging the industry to move toward standardized, auditable interfaces.

In the context of AI agents, this includes two key technical enablers: intent frameworks, which help agents parse user goals and translate them into structured actions within apps or operating systems; and function calls, which allow agents to interact directly with backend services or APIs—bypassing the need for brittle screen scraping or simulated UI interactions.

Yet Chinese tech players have made visible progress in intent frameworks and function calls, many still pair these with accessibility-based workarounds.

Meantime in the US, protocols like Anthropic’s MCP and Google’s A2A are laying the groundwork for a scalable, interoperable agent ecosystem—moving from solo tools to coordinated networks. MCP gives agents the ability to use tools safely; A2A gives them a common language to collaborate. Together, MCP and A2A push agent design from isolated assistants toward an extensible, networked architecture—an essential leap for long-term scalability.

While companies like Baidu and Alibaba have begun exploring MCP style protocols, through initiatives like Baidu’s Qianfan and Alibaba's Model Studio, the pace as a whole remains slow and fragmented. Most implementations so far are partial and exploratory, focusing on peripheral services rather than core transactional functions.

Key consumer-facing platforms such as WeChat, Meituan, and Douyin have yet to meaningfully participate. In many cases, what is labeled an MCP server is simply a repackaged API with limited capabilities, often read-only or narrowly scoped. This reflects not just technical immaturity, but also a deeper reluctance among major platforms to loosen their grip on data, traffic flows, and monetization models.

China’s current reliance on GUI manipulation and system-level shortcuts puts it at risk of missing this deeper infrastructure wave. If Chinese developers want a seat at the table when global agent standards are written, the time to shift course is now.